Pelvic floor dysfunction encompasses a wide variety of medical diagnoses and clinical presentations. As a patient, navigating healthcare professionals in this area can be a very frustrating and time consuming process. This process can take months, or even years, to find the right provider with the right tools to help improve overall quality of life. Not to mention, there is a certain cultural ‘taboo’ that surrounds discussions regarding dysfunctions of the pelvis.

How easy is it for you to ask your friends or loved ones if they also experience pain with sex? Or if they leak urine when they laugh, sneeze or exercise? Or if they have pain in their unmentionable regions with clothing wear or simply sitting? Not to mention, most people wouldn’t even consider talking about dysfunction that involves a bowel movement. In addition to the cultural taboo that surrounds this region, there are many practitioners who shy away from treating pelvic floor dysfunction with the assumption that treatment isn’t “in their wheelhouse.” While this might not be in your comfort zone anatomically, let’s think about this logically…

How easy is it for you to ask your friends or loved ones if they also experience pain with sex? Or if they leak urine when they laugh, sneeze or exercise? Or if they have pain in their unmentionable regions with clothing wear or simply sitting? Not to mention, most people wouldn’t even consider talking about dysfunction that involves a bowel movement. In addition to the cultural taboo that surrounds this region, there are many practitioners who shy away from treating pelvic floor dysfunction with the assumption that treatment isn’t “in their wheelhouse.” While this might not be in your comfort zone anatomically, let’s think about this logically…

Every patient has a pelvis and every patient has a pelvic floor, so rather than dismiss this anatomical region, familiarize yourself with it. Let’s stop putting the “pelvic patient” on their own island and start bridging the gap between the neuro-orthopedic and pelvic worlds.

Let’s Get Nerdy: Anatomical Impacts

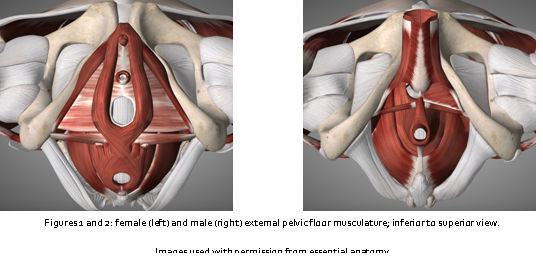

Back to the basics; let’s discuss the anatomy. The term ‘pelvic floor’ identifies the compound structure which closes the bony pelvic outlet, while the term ‘pelvic floor muscles’ refers to the muscular layer of the pelvic floor1. A heathy pelvic floor functions as a synergistic network of muscles, nerves, and connective tissues to support our pelvic organ systems, contributes to core stability, and is largely responsible for maintaining function of our bowel, bladder, and sexual systems. The urethra, vagina, and rectum pass through the pelvic floor and are surrounded by the pelvic floor muscles, so this makes sense, right?

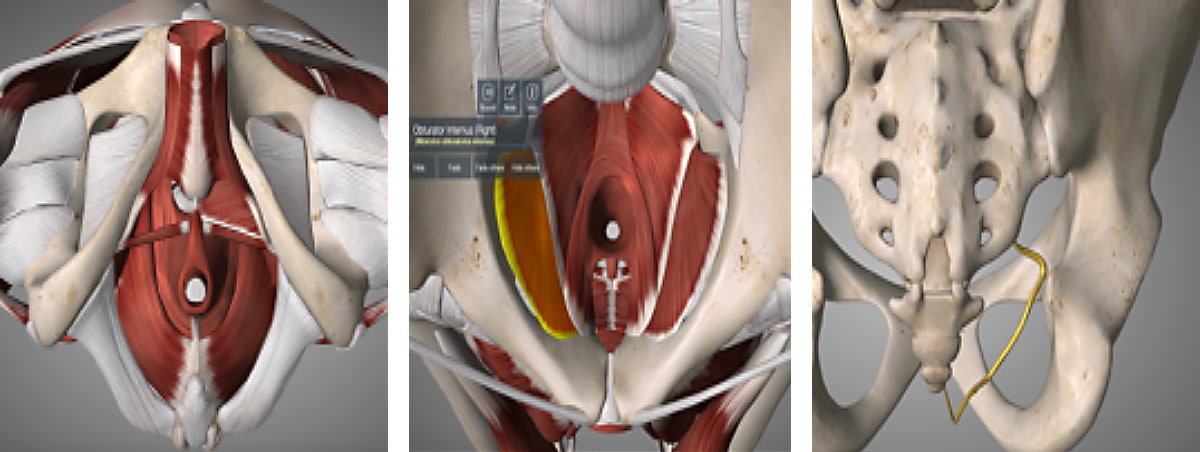

The group of muscles that comprise the pelvic floor musculature includes the urogenital sphincter, external anal sphincter, bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus, superficial and deep transverse perineal muscles, levatorani (puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus), coccygeus and obturator internus. All of these muscles, with the exception of the obturator internus, are innervated by the pudendal nerve, originating from the sacral nerve roots S2-S4. The obturator internus is innervated by the nerve to the obturator internus, originating from the sacral plexus, L5-S2. Did that take you on a trip down memory lane back to the one glorious hour of physical therapy school that reviewed the pelvic floor? Welcome back, my friends… Welcome back.

While the pelvic floor itself may be overwhelming to the clinicians who don’t specialize in this area, let’s not forget how much the pelvic floor can impact the kinetic chain. When you appreciate all that attaches to the bony pelvis, it becomes even more impactful. These are structures that you are likely already addressing in patient treatments and plans of care. The abdominal wall, diaphragm, thoracolumbar spine, sacrum, and the anterior, lateral and posterior hip complex to name a few. If any of these regions are dysfunctional, it is going to impact how well the pelvic floor can function.

The Clinical Side of the Pelvic Floor

Pelvic floor pathology comes in a variety of diagnoses, etiologies, and presentations. Patients are often referred to physical therapy with medical diagnoses such as: chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS), interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, endometriosis, dyspareunia, pudendal neuralgia, bowel and urinary incontinence, and chronic prostatitis,2-4. Symptom presentation is quite varied, but often include dysfunctions of the bowel, bladder, and sexual systems, while incorporating varieties of neuromusculoskeletal dysfunctions as well. That being said, a multidisciplinary approach is obviously crucial to tailor treatment specific to each patient’s pathology, symptomatology, and clinical presentation5. Many of these patients have seen a variety of gynecologists, urologists, and gastroenterologists without successful symptom mitigation and are being referred to physical therapy as a last resort.

Pelvic floor pathology comes in a variety of diagnoses, etiologies, and presentations. Patients are often referred to physical therapy with medical diagnoses such as: chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS), interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, endometriosis, dyspareunia, pudendal neuralgia, bowel and urinary incontinence, and chronic prostatitis,2-4. Symptom presentation is quite varied, but often include dysfunctions of the bowel, bladder, and sexual systems, while incorporating varieties of neuromusculoskeletal dysfunctions as well. That being said, a multidisciplinary approach is obviously crucial to tailor treatment specific to each patient’s pathology, symptomatology, and clinical presentation5. Many of these patients have seen a variety of gynecologists, urologists, and gastroenterologists without successful symptom mitigation and are being referred to physical therapy as a last resort.

Let’s focus on the patient referred to us with chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS). Epidemiological data suggest that chronic, widespread, nonspecific musculoskeletal pain is on the rise and has doubled in the past 15 years, affecting approximately one third of the adult population in the US6,7, while Zondervan et al. reports that the estimated lifetime occurrence of CPPS is 33%8. Naturally, it seems like an appropriate place to begin.

We need to first consider that the term “pelvic pain” can mean many different things to our individual patients. In fact, pelvic pain has been associated with over 70 different diagnoses that often present with overlapping physical, functional and psychological components3. This can, no doubt, lead to variability in clinical presentation, so keep that in mind as this “typical patient presentation” can look quite different from patient to patient.

Often, a patient referred to us with CPPS will present with the following symptoms and/or clinical findings1-5,9,10:

1) low back, hip, and/or pelvic pain

2) muscular imbalances in the lumbopelvic and hip complex

3) postural asymmetry

4) bowel, bladder and/or sexual dysfunction

Treatment of three of those findings should be very familiar to each and every clinician. Which of the four would make you most uncomfortable to treat? Number 4? That makes you and most other clinicians not familiar with these conditions and presentations! A key point to consider is that treatment options to a majority of those findings don’t include internal assessment and management of the pelvic floor musculature, which is why many clinicians will not identify with treating pelvic floor dysfunction. Are you starting to tally up how many patients have not completely resolved because, perhaps, we were incomplete in our management?

Next Up: What Does Management Look Like?

There are going to be varying approaches to how we sequence treatment with this particular patient presentation. Do we start with posture? Do we start with the muscle imbalances? Do we address the pain? One approach isn’t necessarily better than the next and how we decide to treat these dysfunctions will be heavily influenced by our clinical experience and training. We can also argue that there is, no doubt, conflicting evidence for each and every treatment approach out there. That being said, I am going to provide you with a more global approach as to how we might treat this patient and not necessarily how to sequence each and every session.

There are going to be varying approaches to how we sequence treatment with this particular patient presentation. Do we start with posture? Do we start with the muscle imbalances? Do we address the pain? One approach isn’t necessarily better than the next and how we decide to treat these dysfunctions will be heavily influenced by our clinical experience and training. We can also argue that there is, no doubt, conflicting evidence for each and every treatment approach out there. That being said, I am going to provide you with a more global approach as to how we might treat this patient and not necessarily how to sequence each and every session.

We all know that our patient with a history of chronic pain is most interested in discussing their pain itself (and don’t worry…they have a “really high tolerance”). Pain is a multiple system output that is activated by the brain based on perceived threat7. I have found that by combining patient education, dry needling, manual therapies, and neuromuscular re-education, we can provide quite a powerful treatment approach for pelvic pain. Starting with tactful educational strategies to address the neurophysiology and neurobiology of pain and relating this to the unique individual’s experience has been a meaningful place to begin. Once we can justify the “why” behind the patient’s symptoms, we can then utilize dry needling and other manual therapies to assist in further mitigating the pain response and thus improving the client’s overall level of dysfunction long term.

The “Why” Behind Our Treatments

A large percentage of chronic pain begins when tissue and/or nerves are damaged in the periphery11. Manual therapies may help to desensitize the peripheral nervous system and surrounding soft tissues by providing neural input to alter the source of the pain11,12. These techniques, whether you’re using joint mobilizations, soft tissue release, myofascial techniques, tool assisted therapies, or any other manual approach, are likely addressing local tissue issues that may be perpetuating chronic pain.

Dry needling is another technique we can utilize to modulate the central and peripheral nervous systems12. There are many theories and conflicting evidence surrounding how this actually happens in the body. While the analgesic mechanism of dry needling is still not well known, we have seen more and more evidence that supports the use of this treatment in our practice. Overall, it is thought that dry needling may address hypersensitive neural structures and spinal segments4, enhance treatment of myofascial pain and trigger points in the pelvic floor and surrounding musculature12-24, and assist in the facilitation and/or inhibition of abnormal muscle tone and motor recruitment patterns25.

How About A Clinical Example?

55 year old male referred to physical therapy with 5 year history of CPPS. His chief complaint is persistent pelvic pain in the peri-anal region, perineum, and along his sacrum, right worse than left. Subjective report reveals pain started approximately 5 years ago following bout of influenza after international travel. Patient reports that over the course of 5 years he had seen 3 urologists who diagnosed him with chronic prostatitis and 1 gastroenterologist who diagnosed him with irritable bowel syndrome; he was treated with 4 different courses of antibiotics without symptom relief. Upon non-resolution of his symptoms, the medical team stated “there is nothing wrong with the prostate and we have exhausted all avenues, maybe the pain is in your head”. Discouraged with this response, he then did his own research and self-referred to a 4th urologist who specializes in CPPS. Following the evaluation, he was diagnosed with CPPS and referred to physical therapy. Upon evaluation, the patient disclosed additional symptoms of interruptions in urinary stream, urinary hesitancy, post void dribble, constipation, and difficulty maintaining and achieving an erection. Patient works as a software engineer and sits at his desk 8-10 hours/day.

Objective findings at evaluation

Specific objective findings can be seen in the chart below. Gross clinic presentation includes the following: abnormal posture, limited and painful functional movements, increased fatiguability and impaired recruitment of bilateral L5-S2 myotomes, muscle imbalances, impaired joint mobility in thoracic spine, lumbar spine and left hip, impaired coordination and weakness of the abdominals, lumbar spine and pelvic floor musculature and tenderness to palpation in the abdominal wall, posterior hip and pelvic floor musculature.

|

Standing Posture |

Functional Mobility |

Myotomes |

|

posterior pelvic tilt |

75% cervical flexion, 50% cervical extension and bilat rotation |

positive bilat L5, S1 and S2 |

|

forward head, rounded shoulder |

50% lumbar flexion |

|

|

kyphosis thoracic spine |

25% lumbar extension, painful |

|

|

flattened lumbar spine |

50% multisegmental rotation bilat |

|

|

Neuromuscular |

PROM/Joint Mobility |

Pelvic Floor* |

Palpation |

|

abnormal hip extension firing pattern, glute max strength 3+/5 |

firm capsular end feel with passive L hip internal rotation |

hypertonia bilat obturator internus, levatorani |

TTP glute med and min bilat, R worse than L |

|

positive Trendelenburg with SLS bilat, glute med strength 3/5 |

tight muscle end feel with bilat passive hip external rotation |

2/5 muscle strength |

TTP obturator internus, deep hip rotators bilat, R worse than L |

|

impaired coordination of transverse abdominis facilitation |

grossly hypomobile thoracic and lumbar spine |

difficulty coordinating pelvic floor relaxation |

hypertonia and TTP bilat rectus abdominis and obliques |

|

impaired coordination of diaphragmatic breath |

+ Thomas test bilat |

TTP R Alcock’s canal/pudendal nerve |

|

*Pelvic floor muscle examination included both external and internal palpation and evaluative techniques.

Where Do We Even Begin?

There are many places I could begin with this patient, but I chose to address the neuromuscular dysfunction and myotome findings on our first visit. Our first treatment consisted of pain science education, dry needling to bilat L5, S1 and S2 multifidi and bilat glute med and min using electrical stimulation with follow up myofascial release to the thoracolumbar spine and posterior hip complex and joint mobilization to L hip. I also recommended he pursue an ergonomic assessment at work and recommended that he consider purchasing a seat cushion to help to offload the pudendal nerve. His home program consisted of diaphragmatic breathing and stretches for the lumbopelvic musculature.

In conjunction to beginning physical therapy treatment, the urogynecologist prescribed rectal suppositories nightly for one month to manage his condition. The rectal suppositories consisted of a pharmaceutical compound to address nerve sensitivity, muscle spasms and pain.

As I progressed through our treatment sessions I included dry needling to the bulbospongiosus, levatorani, obturator internus and pudendal nerve interface with electrical stimulation with follow-up external myofascial release and internal soft tissue massage and stretching.

I know what you’re thinking…”How did she get a needle there?” Certainly these are delicate and intimate areas, and I do NOT advocate addressing these areas without specific training. Feel free to check out the KinetaCore website for more information on our Functional Dry Needling of the Pelvic Floor course!

This patient experienced symptom resolution and improved bladder, bowel and sexual function in 6 visits with the use of patient education, home program exercises, dry needling with electrical stimulation and manual therapy interventions mentioned above. Two additional visits were used to solidify postural stabilization exercises, ergonomic corrective strategies and an independent home program review, totaling 8 visits. This particular patient currently utilizes his home exercise program to manage

his condition.

Take Home

Pelvic floor dysfunction is a relevant and common dysfunction that clinicians find their patients are experiencing. Moreover, it affects a large percentage of our population, including those patients we might not have considered before. These pathologies are very real, very debilitating, but are also very treatable. To begin our treatment approaches we must first identify these symptoms, then employ a multi-faceted and tailored regime specific to each patient. Within those treatments, dry needling can be a powerful tool that we may utilize to address the neuromuscular dysfunction that exists in our tissues which can, in turn, impact the neurophysiologic aspect of pain; however, we cannot forget about our utilization of other therapies to then reinforce our tissue reset and retrain our patients back to optimal function!

Kelly Sammis, PT, DPT, CLT